“Why do Governor Newsom and Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass care more about violent murderers and sex offenders than they do about protecting their own citizens?” asked Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin.

Last summer, as ICE raids swept through Los Angeles, emergency calls to the LAPD dropped sharply. According to dispatch data reviewed by the Los Angeles Times, LAPD calls for service fell by 28 percent in the two weeks following June 6 compared with the same days in June 2024—roughly 1,200 fewer calls per day. Meanwhile, calls involving suspected domestic violence and family disputes declined by 7 and 16 percent, respectively, after the enforcement campaign began.

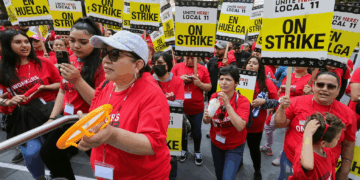

This drop in calls comes amid widespread ICE operations and protests in downtown Los Angeles in early June, a city where about one in three residents is foreign-born. There are several interesting inferences that can be drawn from this data.

One explanation for the drop in LAPD calls holds that ICE raids neutralized criminal elements—i.e., that the individuals removed or deterred through deportation or arrests included those most likely to commit crime. Under this view, the crackdown directly reduced the incidence of property crimes, domestic violence, or street disputes. In other words, fewer calls could equate to fewer criminal acts.

“Under President Trump and Secretary Noem, our law enforcement is working at lightning speed to remove violent criminal illegal aliens from the U.S. Every single day we are arresting gang members, murderers, pedophiles, and violent predators,” said Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin. “70% of ICE arrests are of illegal aliens who have been convicted or charged with a crime. These arrests and deportations of criminal illegal aliens are having a real impact on public safety.”

As of August 2025, Los Angeles County had the fourth-highest number of pending Immigration Court deportation cases in the U.S. with 104,209 cases. Nationally, 470,213 deportation orders were issued by immigration judges in the 2025 fiscal year. While there aren’t any figures on exactly how many deportations have occurred in Los Angeles specifically, one can see there is at least a large enough population to warrant taking this hypothesis seriously.

On the other side is the theory that crime hasn’t really declined, but instead goes unreported because immigrant communities grow fearful of contacting law enforcement. According to this view—which tends to be more popular with those on the Left—undocumented migrants stop calling 911 or requesting police assistance to avoid exposure to ICE or cooperating agencies.

“You’re going to see fear of law enforcement that is going to last generations,” Georgetown University associate law professor Vida Johnson told the LA Times. “And that has the biggest impact on women, because women often are more likely to be victimized, and then more afraid to call for help than men.”

The problem with that hypothesis is that it’s inherently unprovable and difficult to quantify. It’s certainly a possible explanation, but it posits a blanket assertion and then shifts the burden of proof. There’s no audit trail for cases that people decided not to report.

How does one measure acts that weren’t reported?

Further, the theory depends on assuming that unreported crimes rise in exact mirror to reported ones, which can’t be validated. It becomes a convenient political narrative more than an empirically testable claim.

From a logic standpoint, this is a textbook example of affirming the consequent. One sees fewer police calls, so one infers “people are afraid to report.” But that reasoning is flawed because fewer calls could equally be explained by less crime—or other factors. Affirming the consequent treats “if A then B” as if “if B then A” must also hold, which isn’t logically sound.

This fallacy shares a great deal in common with both the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy and the mistaken causal inference (“correlation = causation”) fallacy. Ironically, there are many on the Left who would argue their opponents are equally guilty of the same fallacy. In other words, they might admit that calls to LAPD fell after ICE raids, but insist that this doesn’t prove the raids caused the drop.

But in this case, there is a historical precedent—where targeted enforcement did precede drops in crime.

Long before the Los Angeles Times piece, the the Council on Criminal Justice, an independent non-partisan organization, released a report showed staggering drops in crime since January 20, 2025—when Trump took office and, shortly thereafter, his administration authorized its first round of ICE raids. In particular, homicide decreased by 17%; gun assaults fell by 21%, aggravated assault and sexual assault both went down by 10%; and carjacking dropped by 24%.

And all of that progress has been made in spite efforts by Los Angeles public officials—as well as their allies in Sacramento—directly working to shield illegal immigrants from deportation.

“Why do Governor Newsom and Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass care more about violent murderers and sex offenders than they do about protecting their own citizens?” asked McLaughlin. “These rioters in Los Angeles are fighting to keep rapists, murderers, and other violent criminals loose on Los Angeles streets. Instead of rioting, they should be thanking ICE officers every single day who wake up and make our communities safer.”

In the end, the data leave space for both interpretations, and perhaps both have some truth. The drop in LAPD calls after sweeping immigration enforcement could reflect fewer crimes—or it could reveal that illegal immigrants are allowing crime to go unreported. Readers should draw their own conclusions.